The Death of a Discourse January 30, 2015 – Posted in: Uncategorized

The Death of a Discourse

With American hegemony firmly established, now we hear of an American Islam which, as Iran’s spiritual leader Ali Al-Khamnaei has complained, is ‘a backward Islam that falls in line with American principles and Western ideals’. Khamnaei and other leaders of the Muslim world have reason to worry. The recent years have witnessed an upsurge in modern day messiah of Muslims who look at Islam from the tainted glass of American foreign policy and call Mr.Bush ‘the Muslim World Savoir’. To them or perhaps more appropriately for them, ‘Bush is bringing liberation, not war’. We have Muslims in America who would openly advocate, nay rather incite, that ‘an invasion of Iraq would be the single best path to reform Arab world’. Then there are enthusiasts ready to fight in Iraq ‘with America’ and ‘for America’ as they see it a ‘divine commitment’, ‘a covenant with the nation’. This, then, is American Islam.

Judging from the buzzword in Riyadh, Cairo or Islamabad, this Muslim passion for America is not even on the fringe, though. The stronger and dominant voice of Islam sees in Iraq a conflict not only between the oppressor and the oppressed, colonizer and the colonized, more so they look at it as a battle between Islam and Kufr, a Jihad activity. What goes on in Iraq is indeed a painful scenario but looking at it in black and white will be an oversimplification of the whole complex multi-faceted issue. Among the Bathists, the Islamists, the nationalist are also people who have discovered in the resistance movement an opportunity for advancing their own petty agenda. True, imperialism of any sort must be resisted but in order to support and strengthen the resistance we need not twist religious dicta. For tomorrow if the final outcome is different from the one expected of a Jihad – and this is very likely in the Iraqi case as it happened in the Mujahedeen’s Afghanistan – it will only add further disillusionment to the Islamist’s camp. The neo-Wahabi Ulema who have recently issued a fatwa declaring Resistance in Iraq a purely Islamic Jihad, a religious obligation on the faithful, have gone a bit too far in their love for Iraq. However, the neo-Wahabis are not alone in their use, rather misuse, of religious vocabulary. The same is true with the mainstream Ulema and religious organizations. They have either lent their credibility to the Jihad fervour or preferred to keep quite ‘in the greater interest of the Ummah’.

The issue we take up here for consideration is not which side of the conflict one should be on, but about how our religious sensibilities should be put to work with honesty and vital issues be undertaken with an open end. Intellectual dishonesty or carelessness may appear to be enhancing a struggle for the time being but in the long run it shakes the very ideological foundation that we stand on. The fatwaic vocabulary, intended to suppress any healthy discussion, has left the concerned Muslims in tatters; how come the same Islam that allows Muslims of the American variety to fight for America in Iraq may ask Muslims of other parts of the world to put a fierce resistance to the same invading army?

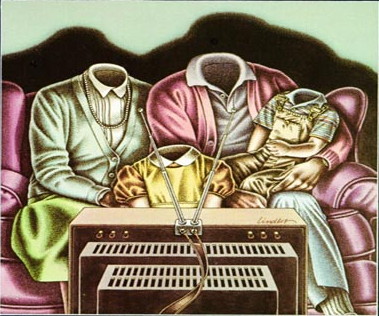

Be they upholders of the American Islam or their Wahabi counter parts or even the religious seers in Islamic Iran, they equally miss the point that instead of looking at the issue afresh, and in the Qur’ani paradigm, they have been rather mislead by a fatwaeic epistemology that leaves no room for any further enquiry or creative debate. Fatwaeic thinking is not necessarily loaded with fiqhi jargons; it is a closed-mind set that denies any need for reconsideration. The fatwaeic mind relies mainly on its personal whims, likes and dislikes. This closed mind-set has virtually ruled out any possibility of a creative debate within the Ummah on issues of vital importance bringing us to a dead-end, a situation that may rightly be termed as the death of a discourse. And this in fact is the mother of all crises, a vicious circle where the Ummah is trapped in for many centuries. The situation demands that we look at the Qur’an afresh, in our own specific context, to discover a fresh answer. But the death of a creative discourse amongst us rules out any such opportunity.

Let us explain. In Pakistan, during Ayyub Khan’s Presidency, the issue was tabled for a public debate that if Pakistan had to become an Islamic state which of the four or five schools of fiqh was to be given official patronage. The Ulema notwithstanding fully aware of the destructive potential of the question simply preferred to evade any serious enquiry into the crux of our malaise saying that the fiqh hanafi as being the fiqh of majority of Pakistani Muslims should get the official status. We conveniently ignored the fact that those who adhere to a particular school of fiqh do so because they think that their school of fiqh is closer to the truth and therefore they will not be willing to give up their version of the truth. The creation of modern Pakistan and the new realities in the twentieth century were demanding from thinking Muslims and Ulema a thorough probe into the psychological, historical and the socio-political bases of the conflicting fiqhi schools that look at the Revelation as a codified, nay rather fossilized instructions, leaving no room for a purely Qur’anic discourse to start afresh. Had this process of enquiry been initiated in independent Pakistan the country would certainly wore a different look today.

We should not loose sight of the fact that the Qur’an is an ever-continuing discourse, an invitation to think, enquire, and keep formulating till an unachievable perfection. In the Qur’an, the oft repeated qul (say) in response to qaloo (they ask) is indicative of the fact the Qur’an does not require from us to be a prisoner of fatwaeic mind set. Instead, it demands from us to keep our hearts and minds always open (ام على قلوب اقفالها) and make good use of the reasoning faculties. Every individual is required to employ his own mind. Relying solely on the wisdom of the dead is a non-starter for seekers of truth. Salaf worshipping, no matter whosoever pious our Elders had happened to be, is no different from the mental slavery of the Mushrekoon that receives God’s utter condemnation: وجدنا آباءنا كذلك يفعلون The process of self-enquiry and the discourse on Man’s role and position in the universe does not stop even after one’s submission to God. A deeper understanding of the universe and the awe that such an understanding brings to a God-fearing heart empowers the individual for a leadership role:انما يخشى الله من عباده العلماء. The believer, as he is an integral part of the Qur’anic discourse is never weary of a creative answer, not even in wavering moments of crises: ام حسبتم ان تدخلواالجنة ولما ياتكم مثل الذين خلوا من قبلكم مستهم الباساء و الضراء وزلزلواحتى يقول الرسول والذينءامنوامعه متى نصرالله الا ان نصرالله قريب.

The death of an internal debate within the Ummah has in fact left us fragmented. The sublime Revelation of the Qur’an, the uniting cohesive force of Tawhid has been so fenced and re-fenced by the fuqahah and mufassiroon, by the historians and the mohaddisoon, that a fresh and creative approach to the Qur’an is made almost impossible. The fences are so effective that in our enthusiasm to go by the Qur’an we eventually find ourselves drawn to a mindless imitation of the Salaf Saleheen. And this is certainly a replica of a dead nation that once was deprived of her originality and creative thinking and condemned to live a life in aping: كونوا قردة خاسعين

An internal debate within the house of Islam holds promise of pulling down the pseudo-religious identities such as Hanafi, Shafei, Maleki or Hambali etc. Had we inherited a continuing discourse from the great fuqaha whom we look at as sacred sources of religion, a set of divinely ordained people, the situation would certainly have been quite different. We cannot simply turn a blind eye to the historical factors responsible for the canonization of the four schools of fiqh in the 9th century. The canonisation or recognition of the four schools among some forty existing schools was a compromise formula intended to end the internal strife. It cannot and should not be taken as a divine scheme. If the four great scholars of the past can be given the right to formulate a code of living for us based on their specific understanding of the Revelation, can we deny the same honour to a fifth or a sixth capable individual simply for their late arrival in history? No doubt, there have been some serious attempts in the past to roll back the culture of fossilised discourse. From Al-Zaheri to Ibn Hazm and from Ibne Taimiaya to Mohammed bin Abdulwahhab attempts were made to break the deadlock in Islamic thought. Though inherently non-starters, as these efforts were, nevertheless, they paved way for future reform activities. One should not downplay the iron-fist unity that the Wahabi Islam was eventually able to bring to the holy Harem in Makkah reducing the four simultaneous fiqhi prayers into one. However, the movement once so full of life and vigour gradually turned their revolutionary icons like Ibne Taimiyah and Mohammed bin Abdulwahab into cult leaders, belittling all hopes for a return to the pristine purity of Islam.

The virtual closure of the Qur’an and building interpretative fences around it eventually resulted in the closing of the Muslim mind. Muslims of the later centuries had no option but to breathe in the fiqhi milieu of the Abbasid Baghdad. Living in the 21st century we have an uncomfortable feeling that those who command our religious life are the great seers of the past, long dead and who cannot be blamed for not knowing enough of our specific context. For centuries we Muslims are without a living leader, without a living mind to interact with the Qur’an: يا رب ان قومى اتخذوا هذا القرآن مهجورا

The Prophet has assured us, as the tradition has it, that Allah will elevate the nation that upholds the Qur’an. One wonders, why then the Muslim Ummah lags behind and always find itself on a slippery-slope. None can match our passion for the Qur’an; from its careful recitation and memorization to the distribution of nicely printed and decorated copies. We have built a tradition that no other nation can boast of. Yet we are an ailing nation knowing not what it really amounts to uphold the Book of God. As most of us have come to regard the extra-scriptural material as a natural extension of the Qur’anic worldview, we mistakenly hold that the fiqhi recreation of Islam is a mere simplified version and the implementation of the fiqh, though juristic dicta of the past can be as good as the Qur’an itself. Such mistaken notions that hold human interpretative activities infallible create serious misgivings about the nature and scope of any future Muslim civilization.

Our elevation through the Qur’an is only possible if we are willing to interact with the Qur’an on our own and have the guts and courage to accept the challenge of Revelation. The Qur’an is an open invitation, an all-embracing book, a solace for the entire mankind. It calls for open-mindedness, greater tolerance, respect and acceptance of the other, justice and dignity for all. The true Tawhidi paradigm enables the believer to look at the entire human race as children of one God in need of solace and salvation, and at himself, by virtue of a follower of the Prophet, as a benefactor to the humanity. The nations that control the world today are probably better embodiment of these ideals than us. And this is the secret of their leadership role. While we, torn in hair-splitting fiqhi debate, find it difficult to grant the same right to dignified living to people of other faith communities or even Muslims of a different hue. The fall of the Taliban was an emotional setback for the Ummah, but it was very much along the SunnatAllah, the laws of nature. Those who cannot embrace their own brothers and sisters in faith how can they be entrusted with the responsibility of global leadership? Away from any fiqhi interruptions or interpolations we must recreate the universal Qur’anic vision of peace and justice for all. Unless we make a decisive return to the Qur’an the conflicting versions of Islam will keep us haunting and the much chanted slogans like ‘Islam is the solution’ or ‘Qur’an is the Answer’ will remain zombiefied and Muslims will be seen as a fossilized nation where a creative intellectual activity has come to an end.

Rashid Shaz